Handling Sensitive Questions in Surveys and Screeners

my notes ( ? )

Frequently, surveys and screeners contain questions that some respondents may find sensitive or be reluctant to answer. Even questions that might seem innocuous to a researcher, like age, gender, or income level, could cause an emotional response from your respondents.

This article guides you through handling sensitive questions in surveys and screeners and provides some example wording for you to use in the future.

In This Article:

Which Questions Are Sensitive?

Researchers should always attempt to avoid any possible discomfort experienced by their research participants. In addition to the obvious ethical implications, sensitive questions could cause participants to either abandon the survey or, worse, provide unreliable answers.

A sensitive question is one that respondents might find embarrassing or invasive.

There are multiple categories of sensitive questions to be aware of, but two are particularly worthy of consideration for user researchers: demographic questions and questions about socially undesirable behaviors.

Demographic Questions

Survey researchers often add demographic questions to a questionnaire without considering how they might be construed. While many survey takers might breeze through demographic questions, they can be potentially triggering or offensive for some respondents.

Demographic questions that have the potential to be perceived as sensitive include those asking about:

- Age

- Sex

- Gender

- Race

- Ethnicity

- Religion

- Income level

Income level can be especially problematic and lead to high rates of nonresponse. One study by Jeffrey Moore and colleagues found that questions about income are 10 times more likely to be left blank than other demographic questions.

Sex and gender are other categories of questions that can be sensitive depending on one’s gender identity. Take this question from a recent Nielsen Radio Ratings survey.

Many people would easily complete this question without a second thought. However, consider this account from genderqueer essayist s.e. smith:

“For some trans* folk, it is a place of endless heartbreak. Every. Single. Time. I fill out a form, I stop here. There is a long pause. A hesitation. A sigh. I am not male. I am not female. On paper forms, I often leave it blank [...]

Imagine dreading the filling out of forms not because it’s a hassle and it’s repetitive and it’s not very fun. Imagine dreading it because you know that you are going to have to lie and erase yourself every time you fill out a form.”

User researchers like to refer to themselves as user advocates. This lofty designation extends not only to designing delightful user experiences and interfaces but also to protecting the human experiences of our research participants. This includes all participants, not just those that fall into a perceived norm.

Questions About Socially Undesirable Behaviors

Social-desirability bias is a cognitive bias that dictates that people are less likely to disclose behaviors or preferences that are deemed to be undesirable by society. Behaviors that are considered socially undesirable can vary from person to person and, therefore, are likely to slip undetected through a survey creation process.

Common behaviors known to lead to underreporting in surveys include:

- Alcohol consumption

- Cigarette smoking (especially during pregnancy)

- Abortion

However, there are less obvious behaviors as well. For example, voting is also considered a socially desirable behavior, and in many surveys, the reported voting rate is higher than the real one.

Beyond these categories, additional topics that might include sensitive questions include the following:

- Questions about illegal activity

- Identifying information (e.g., home address)

- Emotionally upsetting topics (e.g., health concerns or victimization)

- Information that might be threatening in the wrong hands (e.g., disclosing a preexisting health condition)

Guidelines for Handling Sensitive Questions

While the strategy for addressing sensitive survey questions will vary based on multiple factors, some general guidelines are always helpful.

Determine if You Really Need to Ask

Researchers frequently include demographic questions in a survey just out of habit, without considering whether asking is truly necessary. To optimize response rate, surveys should be kept as short as possible, and therefore any question should be included only if necessary for the research at hand.

Here are 2 questions you should ask yourself before including any question in a questionnaire, regardless of sensitivity.

- Do You Truly Care About the Answer?

Don’t ask questions because you’re merely curious, or assume all questionnaires should include basic demographic questions. If you have no plans to make decisions based on the outcome, you probably shouldn’t include the question.

- Can You Find the Answer Another Way?

Are you using a recruiting panel like UserTesting.com or User Interviews? If so, a lot of demographic data about respondents is already included in their profiles and, therefore, doesn’t need to be asked.

Are you asking about browsing behavior on your site, data that could be gathered more accurately from analytics? Don’t ask users to provide you with information that you can access in another, less intrusive way.

Emphasize Confidentiality and Anonymity

Whether to keep participant data confidential, anonymous, or both is an important consideration in survey methodology. While often conflated, these two terms describe two different concepts.

Anonymity means a participant's data cannot be traced back to their identity. Ensuring anonymity may mean using a pseudonym or code number instead of the participant’s name in reporting.

Confidentiality limits the people who are permitted to view the response. Ensuring confidentiality might mean that no one beyond the immediate research team will ever view the survey data.

Anonymity is typically required in most cases of user research, and confidentiality is typically overkill. That said, adding the promise of confidentiality can sometimes increase the likelihood of complete and honest responses to sensitive questions.

Respondents should never have to guess whether a survey is anonymous, confidential, both, or neither. This information should be readily available to respondents when they are deciding whether to take the survey. For example:

Your privacy is important to us. All responses to this survey will be kept strictly confidential. Individual answers will be anonymized and aggregated for analysis. Your personal information will not be shared with any third parties, and will only be used for the purpose of this research. Thank you for your participation.

Lead Up to Sensitive Questions

Sensitive questions placed too early in a questionnaire or screener are more likely to lead to dropoffs. Build respondent trust with nonsensitive questions first, allowing them to invest effort in the process.

This guideline also applies to demographic questions, which should be optional and placed at the end of a questionnaire, not at the beginning, as is often the case. Demographic questions at the beginning are much more likely to lead to dropoffs than demographic questions at the end, even when they are not deemed to be sensitive.

Also, avoid placing particularly sensitive questions at the very end of a survey. If you inadvertently offend a respondent, you don’t want that to be their lasting impression of the survey.

Provide Context and Use “Question Loading”

UXers love to remove unnecessary text from interfaces and forms. Sometimes, however, adding more information is necessary.

First, you may use question loading (not to be confused with a leading question). Question loading is the inclusion of additional context that may assuage respondent guilt or shame around questionable behavior.

Original question: Do you save a portion of your income each month?

With question loading: Given the rising cost of living and various financial commitments, many people find it challenging to save regularly. How often are you able to save a portion of your income each month?

Additionally, if a question or topic may raise eyebrows, consider explaining the purpose of asking it and the benefit that could come from answering it honestly. For example, if a survey asks a question about abortion, the drafter may include language such as the following:

We are conducting a survey to understand people's experiences with abortion. Please know that your responses are completely anonymous and will be used solely to improve access to abortion care for those who need it. We approach this topic with sensitivity and without judgment.

Use Ranges Rather than Specific Values

Imagine you want to ask about someone’s income — something they may reasonably feel sensitive about sharing. Imagine someone’s reaction to reading the following question:

What is your annual household income: __________

A respondent would likely feel very apprehensive about sharing their specific income for several reasons. They may:

- Worry about how their income will compare to the rest of the sample and whether they would be an outlier on either end of the scale

- Be confused about input formats (Do I include a dollar sign? Do I include “.00”? Do I include “per year”?)

- Worry about whether giving an exact number may be somehow identifying or overly revealing

- Be reluctant to do math if their income is variable or complex

Now consider the following format instead:

What is your total annual household income?

- $24,999 or less

- $25,000 to $49,999

- $50,000 to $74,999

- $75,000 to $99,999

- $100,000 to $149,999

- $150,000 to $199,999

- $200,000 or more

This tweak addresses all the previous concerns. With this question format, a respondent would:

- Have a sense of how their income compares to the range, and hopefully get some reassurance that they are not alone in whatever range they fall into

- Not need to worry about an input format

- Not need to provide an exact number

- Be less likely to need to do math

Ranges feel less sensitive than asking for specific values. The larger the ranges provided, the less sensitive the request feels.

Ask About Frequency Rather than Yes/No Questions

Consider the following question from the 2019 Youth Risk Behaviors Survey.

During your life, how many times have you used marijuana?

- 0 times

- 1 or 2 times

- 3 to 9 times

- 10 to 19 times

- 20 to 39 times

- 40 to 99 times

- 100 or more times

Rather than simply asking Have you ever used marijuana? (which, admittedly, would probably have been easier for respondents to answer correctly if they had been willing to share that information), the researchers asked about the frequency of use. While the Yes/No formulation may imply a moral judgment and encourage lying, the frequency question makes a slight assumption that the respondent has indeed used marijuana in the past, which encourages honesty.

Additionally, you may wish to provide additional response options at the end of the range that may be perceived as undesirable, to skew the responses away from bias. For example, consider the following question about exercise frequency.

How often do you engage in physical exercise each month?

- 0 to 3 times a month

- 4 to 7 times a month

- 8 to 12 times a month

- 13 to 20 times a month

- More than 20 times a month

Someone who only works out once or twice per month may feel shame around selecting the bottommost option, and dishonestly select a response towards the middle of the range (see central-tendency bias).

The following formulation would likely encourage more honest responses from infrequent exercisers.

How often do you engage in physical exercise each month?

- 0 times a month

- 1 to 2 times a month

- 3 to 4 times a month

- 5 to 7 times a month

- 8 to 12 times a month

- 13 to 20 times a month

- More than 20 times a month

Ask Indirectly

For particularly sensitive topics, researchers may wish to employ an indirect surveying technique, such as the item-count method.

In this approach, the respondent population is divided into two groups. Each group is asked an identical question about how many behaviors from a list they have engaged in, with the addition of the behavior in question for only one of the groups.

For example, consider this question from a 2014 study by Jouni Kuha and Jonathan Jackson at the London School of Economics:

I am now going to read you a list of five [six] things that people may do or that may happen to them. Please listen to them and tell me how many of them you have done or have happened to you in the last 12 months. Do not tell me which ones are and are not true for you. Just tell me how many you have done at least once.

Attended a religious service, except for a special occasion like a wedding or funeral

Went to a sporting event

Attended an opera

Visited a country outside [your country]

Had personal belongings such as money or a mobile phone stolen from you or from your house?

Treatment group only: Bought something you thought might have been stolen

During the analysis, the research will then compare the differences between the two groups in order to estimate the frequency of the behavior in question.

Embed the Sensitive Question

A single sensitive question in an otherwise mundane questionnaire can stand out and be jarring. Researchers may attempt to disarm the respondent with other slightly sensitive questions to mask the question of interest.

Specific Question Wordings

Some questions (e.g., demographic questions) are very common and potentially sensitive. The following section includes recommendations for specific wording for these questions. You are welcome to utilize these wordings in your own surveys and screeners.

Sex and Gender

Sex and gender, while frequently conflated and confused, are different (sex is biological characteristics, whereas gender is one’s social identity). The first question you need to ask yourself when asking about sex or gender (after asking, “Do I really need to be asking at all?”) is, “Which one do I care about?” Most of the time, UX researchers care about gender, not sex.

The most important thing to remember when asking about gender is to use inclusive and gender-expansive language that captures the full breadth of gender identity that society now recognizes.

First, consider the question wording. Please select your gender implies that one of the options provided will be a perfect match for the respondent’s gender identity and, therefore, requires the inclusion of an Other:_______ option.

On the other hand, Which of the following best represents your gender? implies only a best fit, so the use of a fill-in-the-blank Other option, while still advisable, is not required.

Next, consider the options provided. It is no longer acceptable to limit gender identity options to simply man and woman. Society’s understanding of gender identity has expanded, and research methods must reflect that.

In most instances, it is sufficient to limit options to the following categories:

- Man

- Woman

- Non-binary

- Prefer to self-describe:_______

- Prefer not to disclose

If you additionally have a need to know whether someone is transgender (e.g., in order to differentiate between cisgender men and transgender men, both of whom would select Man from the above options), ask a followup question:

Do you identify as transgender?

- Yes

- No

- Prefer not to disclose

If you are conducting research for which a granular and inclusive capturing of one’s gender identity is necessary, consider using the following options to the first question and omitting the followup transgender question.

- Cisgender man

- Cisgender woman

- Transgender man

- Transgender woman

- Nonbinary person

- Genderqueer/genderfluid person

- Agender person

- Two-spirit person

- Intersex person

- Prefer to self-describe:______

- Prefer not to disclose

Age

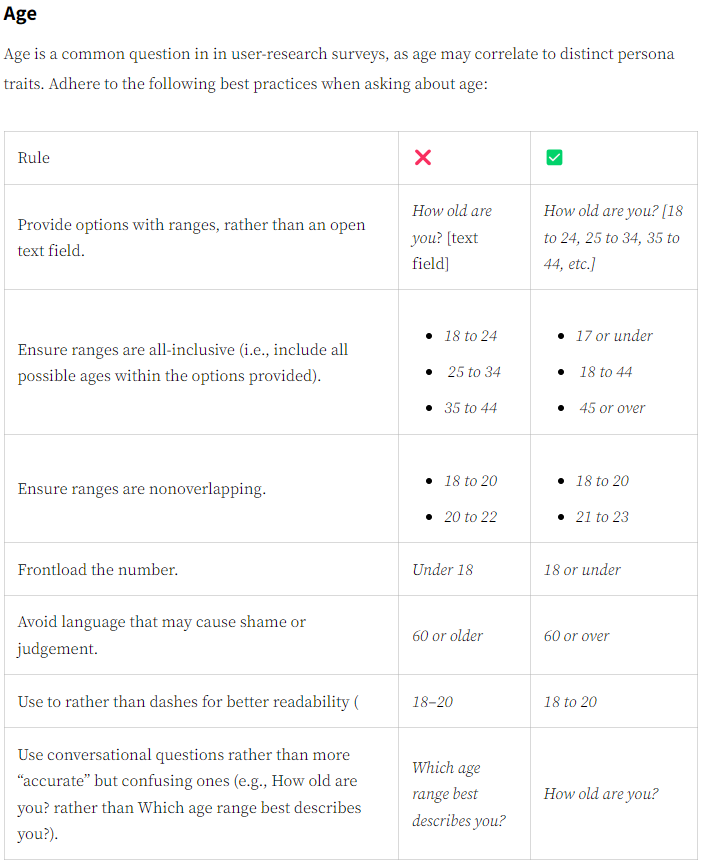

Age is a common question in in user-research surveys, as age may correlate to distinct persona traits. Adhere to the following best practices when asking about age:

Age

Age is a common question in in user-research surveys, as age may correlate to distinct persona traits. Adhere to the following best practices when asking about age:

Rule

✅

Provide options with ranges, rather than an open text field.

❌ How old are you? [text field]

✅ How old are you? [18 to 24, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, etc.]

Ensure ranges are all-inclusive (i.e., include all possible ages within the options provided).

❌

- 18 to 24

- 25 to 34

- 35 to 44

✅

- 17 or under

- 18 to 44

- 45 or over

Ensure ranges are nonoverlapping.

❌

- 18 to 20

- 20 to 22

✅

- 18 to 20

- 21 to 23

Frontload the number.

❌ Under 18

✅ 18 or under

Avoid language that may cause shame or judgement.

❌ 60 or older

✅ 60 or over

Use to rather than dashes for better readability (

❌ 18–20

✅ 18 to 20

Use conversational questions rather than more “accurate” but confusing ones (e.g., How old are you? rather than Which age range best describes you?).

❌ Which age range best describes you?

✅ How old are you?

One recommended wording is:

How old are you? (single select)

- 17 or under

- 18 to 25

- 26 to 35

- 36 to 45

- 46 to 55

- 56 to 65

- 66 or over

Race and Ethnicity

Like sex and gender, race and ethnicity are often confused but are different (race refers to physical traits; ethnicity refers to cultural identity and heritage).

Determine first which you care about. It is possible to formulate questions that ask about race only, about ethnicity only, or about both.

Additionally, be aware that many people identify with more than one racial and ethnic group and will be excluded if you force them to pick one. For this reason, use multiselect question formats for these questions.

Just Race

How do you describe yourself? (multiselect)

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Black or African American

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

- White or Caucasian

- Other:______

- Prefer not to disclose

Just Ethnicity

Are you of Hispanic, Latinx, or of Spanish origin? (single select)

- Yes

- No

- Prefer not to disclose

Race and Ethnicity

You can ask about both race and ethnicity separately, using the two questions above, or you can combine them into a single question:

How do you describe yourself? (multi-select)

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Asian

- Black or African American

- Hispanic or Latinx

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

- White or Caucasian

- Other:______

- Prefer not to disclose

Accessibility Needs and Disabilities

When asking about accessibility needs or disability, do so directly, using language used by the communities in question.

Do you have any of the following accessibility needs? (Select all that apply)

- Cognitive: such as dyslexia or ADHD

- Emotional: such as anxiety or depression

- Hearing: such as deafness or hearing loss

- Motor: such as cerebral Palsy or arthritis

- Visual: such as blindness or vision loss

- Other:________

- No, I don’t have any accessibility needs

Make sure to avoid language that implies negativity (e.g., Do you have diabetes? instead of Do you suffer from diabetes?; Do you use a wheelchair? instead of Are you confined to a wheelchair?).

Language Proficiency

Suppose you need to know about someone’s qualitative assessment of their own language proficiency. In that case, it is helpful to provide a brief description of each answer option to ensure understanding, particularly if the reader is less proficient with the language.

How would you describe your English language level (or proficiency)?

- Native / Mother-tongue: English is my first language

- Fluent: I can speak, read, and write in English fluently

- Proficient: I am skilled in English but not fluent

- Conversational: I can communicate effectively in English in most situations

- Basic knowledge: I have a basic knowledge of the language

References

Groves, R.M., Fowler Jr, F.J., Couper, M.P., Lepkowski, J.M., Singer, E., and Tourangeau, R. 2009. Survey Methodology. 2nd ed. Wiley.

Jarrett, C. 2021. Surveys That Work. Rosenfeld Media.

Kuha, J. and Jackson, J. 2014. The item count method for sensitive survey questions: modelling criminal behaviour. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 63, 2 (Feb. 2014), 321-341. Published by Oxford University Press.

Moore, J., Stinson, L., and Welniak, E. 1997. Income Measurement Error in Surveys: A Review. In Cognition and Survey Research, Sirken, M., Herrmann, D., Schechter, S., Schwarz, N., Tanur, J., and Tourangeau, R. (Eds.). Wiley, New York, 155-174.

smith, s.e. 2009. Beyond the Binary: Forms. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from meloukhia.net/2009/12/beyond_the_binary_forms/.

Read the Full Post

The above notes were curated from the full post www.nngroup.com/articles/sensitive-questions.Related reading

More Stuff I Like

More Stuff tagged demographic questions , surveys , user research , user experience research