Dialogue of the deaf: interpreting the election results (updated)

Imported from the Blogactiv.eu blogging platform, closed without warning in 2021. Links, images and embeds not guaranteed, and comments not displayed.

Over 70% of EU voters did not vote for the EU. Where now?

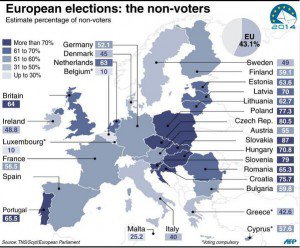

Update, 7/9/14: via Chris Whitehouse - apparently the figures are slightly worse - "the updated numbers, published on the Parliament website, show that turnout across the EU struggled to reach 42.54% in 2014, well below the 43.1% initially announced" ]

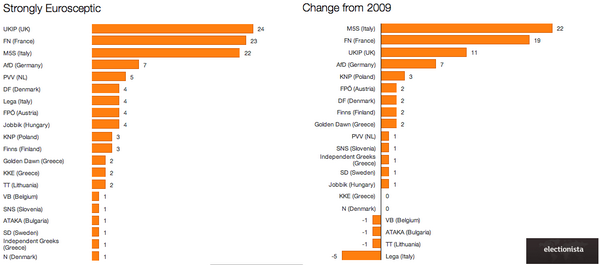

There will no doubt be, as Ron Patz predicted Sunday, endless analyses of the EP 2014 results, with analysts furiously and spuriously spinning results to future advantage. I have neither their agenda nor time and resources for this dialogue of the deaf, so I'll focus on the interrelated issues of abstention (well over the recorded 57%, once you remove the effect of compulsory voting and coordinated elections) and anti-EU votes ("Non attached" + "Others" = 14%).

Interrelated? Surely not! After all, those who abstained just don't care, while those who voted against the EU were motivated! So why lump these figures together?

A: Because of what their total says about EU communications.

The non-voters

Why did 57% of the electorate people not vote? Most would probably give one of 2 reasons:

- irrelevance: they think the EU doesn't matter; and/or

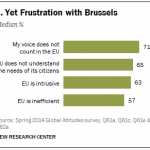

- disengaged: they think their vote doesn't count: I've lost count of the number of polls showing this - the graph is from a recent Pew survey.

Original link

Actually, the 57% figure understates the case - voting is compulsory in Belgium, Cyprus, Greece and Luxembourg, while the 2014 EP election was held with other elections in Belgium, Lithuania and UK (Wikipedia), further boosting turnout.

If we want to really understand the depth of the problem, you need to ask what would have happened without these tricks. I think it's fair to round the non-voters' share up to at least 60%.

The anti-EU vote

Why another 14% of the electorate voted for anti-EU parties, of course, varies in detail by national context. However, we can say two things with certainty:

- irrelevance is not a reason - they believe the EU matters...

- and they also believe it's harming them.

Put the above figures together, what do you get?

Put together, these figures say that:

Around three-quarters of the electorate believe the EU to be

Unimportant OR Harmful

AND/OR Undemocratic

Not exactly a victory for EU communications, which (one would assume) aims to show that the EU is important, that it benefits its citizens, and listens to them.

It appears that around 75% do not agree. Which is a lot. To be frank, it could have been worse.

The first 'social media elections'

These were to be the EU's first 'social media elections' - 5 years ago, most Institutions had not heard of Facebook, the hordes of social media experts had not yet reached Brussels and I was still unconvinced by my first 18 months on Twitter.

How things change. Or have they? For some reason, these results remind me of how one Cabinet staffer answered when I asked what they were going to do with the comments received to a website they were planning: "We'll pretend to listen".

She was young - not the sort of Old Guard Eurocrat you'd expect that from. But before you howl in outrage, remember that her answer reflected the following facts:

- she'd been told by her hierarchy to create a site which was to actively welcome citizen input;

- the people who asked her had not considered the problem of scale;

- reflecting this input into policy would have been profoundly undemocratic.

How many Likes is equivalent to an MEPs' vote, anyway? Should we really re-edit a white paper to reflect Retweets by EN-speaking Twitterati? Seriously?

The perils of over-promising

These results look a little like the #EUCO 'Berlusconi TweetWall experiment' on a continental scale. The greatest Communications Sin is promising to listen to someone and then ignoring them. There is no better way to lose their trust.

Over the last 5 years, the EU Institutions have - in all sincerity - asked for citizens' input, on everything from 'Big Picture Europe' issues to detailed policy questions. Yet in most cases their policy-oriented colleagues were unable to take the ideas on board, and in some cases were busy removing democratically elected governments whose economic plans didn't meet their demands. How on Earth do you propose to reconcile that with a "listening EU"?

The heart of the problem is not new. It is not a question of SEO, or CMS, or multilingualism, or how to fine-tune Facebook posts. It is organisational - Point #1 of 10 things the EU should probably know about social media.

Maybe, over the next 5 years, the EU Institutions will figure out what the role of social media can be - and cannot be - within a democratic EU. It has its place - notably in the development of online communities around specific policies and programmes, and as crucial infrastructure of the EU online public sphere - but it is not the sole answer some appear to think it is. Not figuring this out risks promising more than can be delivered, which will backfire. See you in 2019...

Related reading

More Stuff I Think

More Stuff tagged eurosceptics , trust , egovernment , publicsphere , social media , ep2014

See also: Online Strategy , Online Community Management , Social Media Strategy , Content Creation & Marketing , Social Web , Media , Politics