The UK's GDS meltdown couldn't happen in Brussels, right? (updated)

Imported from the Blogactiv.eu blogging platform, closed without warning in 2021. Links, images and embeds not guaranteed, and comments not displayed.

I freely admit: I've been a fanboy of the UK's Government Digital Service (GDS) since studying their design principles. Those principles are still good. Everything else, it turns out, was not.

I was not the only information architect in Brussels dazzled a few years ago by GDS' approach which, according to internal reports seen by The Register, have now:

"left huge swathes of the British government in disarray...GDS knew its flagship initiative to move all government websites under one roof, GOV.UK, was destroying useful online services and replacing them with trendy webpages bereft of useful information... the digital gurus' lack of any skills or knowledge other than webpage design appears to have equipped them poorly for the tasks in hand ... GDS had a far poorer understanding of what the public actually needed than the relevant government departments did, according to GDS' own internal analysis... GOV.UK has been savaged by users and critics. It’s far less popular with the public than the collection of government sites that it replaced. And arguably more expensive."

- Inside GOV.UK: 'CHAOS' and 'NIGHTMARE' as trendy Cabinet Office wrecked govt websites, The Register, Feb 18, 2015

Given that the GDS advised the EC on revising EUROPA, is this a glimpse of the future?

Original link

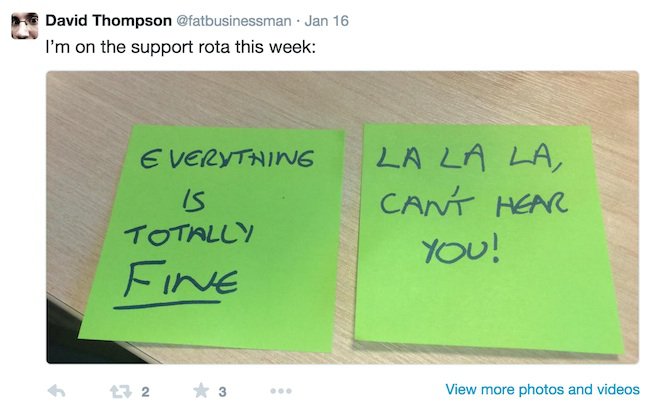

Image from part 3 of The Register's article, which notes that "@fatbusinessman's Twitter bio at the time of writing: 'Geek. Building Internets for Britain at @GDSteam. Sometimes I punch people'"

--- Update: over 2 weeks after The Register's article, GDS finally posts GOV.UK isn’t finished. Judge for yourself, but do note that it doesn't mention or acknowledge any criticism directly, let alone link to the Register - the closest it gets is "A misconception we sometimes hear is that GOV.UK is just for citizens and small businesses, and that the specialist needs of more frequent users are less important. That’s not right".

I find this a mealy-mouthed and frankly dishonest way of addressing criticism - if you're addressing "misconceptions", then you should quote and link to them, not pretend they don't exist. ---

Sound familiar?

First, some history. Most governments' online presence generally sprawl across the web, managed by different, loosely coordinated teams in each Department using different technologies, designs, architectures and more. Inter- and intra-departmental turf wars spill online as managers position their departments, creating overlapping and sometimes contradictory content.

The one thing every site has in common is that they are built around the department's needs, not the users'. EUROPA was certainly like that when I joined the EC in 2001 - I remember:

- meeting 6 members of a DG's comms unit and discovering 6 managers of 6 "portals", mainly brochureware sites. One was a youth portal that didn't - and would not - link to the other EC youth portal managed by another DG

- the EC's central departments developing a centralised, static content management system, in direct contradiction of the stated online policy (decentralised, dynamic), and then trying to impose it by any and all means

- a Head of Unit from DG X literally screaming over the phone at a Head of Unit from DG Y when I was trying to get both DGs to work together on the eBusiness theme (one single page!) of the EC's first thematic portal. Both Units saw themselves as 'chef de fil', of course.

: So it goes. Ancient history now. Right?

Same problem, different shape

The same basic problems - human nature, amplified by organisational rivalry - seem to have manifested in the UK in an entirely different form.

The idea behind the thematic portal model in late 2001 was to leave the DGs' sites - "created by specialists, for specialists" - untouched. Instead, the DGs would cooperate on a user-friendly, multilingual, thematic layer above them to help non-specialists understand the various DGs' activities, thus telling a coherent story about EU Added Value in areas of interest to non-specialists (eBusiness, eHealth, etc.). This brief, stable, multilingual summary then deeplinked users on to the DGs' specialised, monolingual and frequently horrible sites for more details.

It was a pragmatic solution: in 2001, noone had the power to interfere in an individual DG's websites. Nevertheless, fratricidal organisational rivalry killed this architecture, so the move by the UK's Cabinet Office - "creating an untouchable “digital” Whitehall fiefdom in the shape of GDS" to migrate competing sites into one seamless, user-oriented presence - must have looked appealing.

And it certainly helped that GDS made all the right noises about agile development, user-orientation and - of course - massive cost savings. The UK civil service were not the only ones to centralise in this way, but they were definitely the poster child, winning plaudits from around the world. Until now.

Blind arrogance

Because there was just one problem with their centralised approach: the central team not only didn't understand the needs of the various departments' users, they didn't seem to care. Part 2 of The Register's analysis, for example, explores the transition of the Visa and Immigration website into GOV.UK:

"GDS didn’t seem to know who the users of government services actually are ... [and] actually ignored a “request for research” to find out who the users might be... the "jean-wearing Post It Note wranglers” ... didn’t realise that visa applications come not just from tourists, but from universities and business applicants too... The new GOV.UK Visa and Immigration website sent users in circles, making simple processes difficult or impossible.... Entertainers and sports stars were unable to enter the UK."

Oops. So did they learn from this experience? A few months later...

"[despite] switchboards melting ... GDS carried on as if nothing had happened... In December, GDS touted its “big bang” as "over 300 Government sites” shifted to the new portal ... Huge amounts of actual information had been destroyed, while many of the new pages consisted of fluff and filler... really simple things it can't do that (some) older government sites can"

It was, as the BBC put it:

"a calamity for government accountability...It is often incredibly hard (and sometimes impossible) to find older documentation or data. Lots has simply been destroyed. Given that a central role of most government websites is just to publish accountability information, that ought to be an existential problem for the GDS." - A Christmas government website wish, Chris Cook, Newsnight, BBC

This is unsurprising when you realise the dynamics at play here. For one thing, everyone seems to have suffered from a bad case of politics and groupthink:

"politically untouchable, [GDS] quickly assumed supremacy in the Whitehall IT jungle, ... focusing on friendly opinion columnists and political reporters – rather than the technical press, who tended to ask more detailed questions... Coverage was fawning. Civil servants across Whitehall needed to get up to speed with the new jargon fast – buzzwords such as “Agile methodology” and “platforms”.... GDS' prickly response to criticism led one opposition source to describe the new agency as "cult-like”."

A response that went into ballkicking overdrive when the Visa & Immigration fiasco reached melting point:

"GDS even had to bully the Home Office to get it over the finishing line, threatening to give it a “Fail”. This tactic is nowadays familiar in Whitehall – as we saw here, when GDS disparaged the HMRC’s VAT One Stop Shop. The digital wizards at GDS didn’t like the style of the service, so “failed” it. HRMC had no choice but to re-implement a vital tool."

This sounds like classic political infighting - hardly the work of revolutionary digital e-guru maven-ninjas. But then, maybe they're not. After all, their reaction to the BBC article was also classic functionnaire:

Managers forbade staff from Tweeting their indignation back at Cook – and the usually chatty Whitehall office went social media silent.

The GDS blog, which generally averages 2 posts a week, has also fallen silent since The Register's article was published last Wednesday. Maybe I missed the memo. Or maybe, in the end, GDS oversimplified the challenge they faced:

"three software professors and one business professor studied the unit and found (pdf) a "lack of demonstration of complex systems thinking” and “over-simplification of the cultural change required for success”"

I know exactly how easy it is to make that mistake.

We're sexy and we know it (but not much use)

But what really resonated with me was this observation:

"the more specialist the need, the worse GDS failed the users, who were asking, "where has that useful information gone?"".

It's just very hard for any central, general webteam to truly understand the needs of another Department's highly specialised users.

I learnt this the hard way inside the EC around ten years ago. A bit more history: in 2002, I architected the EC's first Web2.0 site for DG INFSO - a Community of Practice for the highly specialised attendees to INFSO's annual 3 day conference, exhibition and networking research event (see Building Communities of Practice with Event-in-a-Box).

The next year we rolled out the Newsroom CMS, allowing staff in different DGs to both publish news, events, publications (and eventually more) on their own site and 'bubble them up' to the shared thematic portal, to be managed using a cross-EC content sharing & notification system.

We knew our users better than anyone; both developments were highly successful. The Event-in-a-Box code has been used every year since, while the Newsroom survived the death of the thematic portal and has just been 'Corporatised' (albeit 12 years later - see All stream, no memory, zero innovation).

But around 10 years ago, the EC's centralised teams wanted to impose a redesign and a CMS which would have made both Event toolbox and Newsroom impossible. I remember explaining users' Public Profiles, user-customised XML feeds, event co-creation and online community management, back-end logistics integration and Newsroom sharing workflows, peer-to-peer messaging services and various other interactive tools, as well as the information architecture needed to make all this usable. And I remember looking at the blank faces and thinking "these guys have absolutely no idea of what our users actually need".

It took me a while to realise that this wasn't their fault. After all, they had good reason to not listen to internal users like INFSO and its communications team. As a central team, they had their own users to think about: the wider public. And that was an important audience for the EU, given that they had just kicked out the proposed EU Constitution. The problem wasn't the people in front of me. It was the way their roles had been structured.

Balancing coherence, usability & innovation

GDS' failure will not necessarily map to Brussels, despite their influence, because there are two critical differences between building national governmental websites and building EUROPA: These differences mean that the cost/benefit calculations of "centralisation v. decentralisation" are different in Brussels, so best practices from national governments cannot be blindly copied across. For the same reason, the failures inherent in GDS' approach may not replicate here. Time will tell.

One fact remains: as any change management expert can tell you, innovation emerges at the edge of large organisations, not the centre. Of course, so does chaos: central control brings coherence, cost savings, and more. The critical challenge in managing any large organisation's web presence is to: centralise where it makes sense to do so; allow innovation to flourish at the edge; and then migrate innovations from the edge into the core.

Needless to say, this is a 100% organisational challenge.

---- Further reading:

- National governments provide a lot of services (passports, driving licenses, etc) to general audiences. The EC provides relatively few services, mainly to specialists;

- Most Europeans understand why their national governments exist, what they do and why. The EU must still bridge this fundamental 'understanding gap'.

- Inside GOV.UK: 'CHAOS' and 'NIGHTMARE' as trendy Cabinet Office wrecked govt websites, The Register

- A Christmas government website wish, Chris Cook, Newsnight, BBC

- Whitehall at war: Govt’s webocrats trash vital digital VAT site, The Register

- So, farewell thematic portals on EUROPA (2009)

- Building Communities of Practice with Event-in-a-Box (2009)

- All stream, no memory, zero innovation (2014)

- A Perspective on the Government Digital Strategy (GDS) (January 2013, pdf)

- Legal Web Watch, January 2015

- 10 posts here partly about groupthink and - for the truly masochistic - 24 resources tagged architecture and 96 more tagged innovation on my TumblrHub.

Related reading

More Stuff I Think

More Stuff tagged themes , europa , gds , euractiv-com , innovation , portal , uncategorized , information-architecture

See also: Content Strategy , Online Architecture , Change & Project Management , Innovation Strategy , Communications Tactics , Business