A Social Filesystem — overreacted

my notes ( ? )

A perfectly brilliant way to introduce AT protocol.

"What do files have to do with social computing? Historically, not a lot—until recently."

Dan first reintroduces files: how they were not originally intended "to live inside the apps... [but] somewhere that you control. Apps create and read your files on your behalf, but files don’t belong to the apps. Files belong to you."

"A manuscript doesn’t stay inside the typewriter, a photo doesn’t stay inside the camera, and a song doesn’t stay in the microphone."

File formats allow multiple apps to read and write them. "Apps and formats are many-to-many... The file format is the API".

But not all are open - .doc is proprietary, but that "didn’t stop motivated developers from reverse-engineering it and creating more software that reads and writes .doc".

But when it came to social, the paradigm changed. "A Tumblr post isn’t a file... But what if they behaved as files... in all the important ways?".

If you had an "everything folder" (aka repository) with all your posts, follows, likes, up/down votes, etc., and these were "social file formats" - files using an open file format - then apps become "reactive to files. Every app’s database mostly becomes derived data—an app-specific cached materialized view of everybody’s folders."

This is not hypothetical - ATproto is a "social filesystem... by lifting user data out of the apps, we force the same separation as we’ve had in personal computing: apps don’t trap what you make with them.

Someone can always make a new app for old data... [while] app developers evolve their file formats... they can’t gatekeep who reads and writes files in those formats. Which apps to use is up to you".

He then gets into a little more technical detail, exploring what a file (or "json record"), identity ("key") looks like, what a lexicon is and how it works, etc.

But what about interoperability? "Can we get the apps to agree with each other? We could try to put every app developer in the same room until they all agree on a perfect lexicon for a post. That would be an interesting use of everyone’s time."

Obviously not. In any case, let people innovate: "it’s actually good that different products can disagree about what a post is! Different products, different vibes... we just need to let anyone “define” their own post". That's why we have collections - "a folder with records of a certain lexicon type".

Investigating the like record type leads to identify, "a difficult problem", particularly as "We need a reliable way to refer to some user" while:

- allowing those users to change where they host their everything folder without breaking any links,

- and ensuring "each piece of data has not been tampered with".

He explores and discards 2 options before turning to option 3, using the global namespace that already exists: "DNS. If dril owns wint.co, maybe we could let him use that domain as his persistent identity... the actual content is [not necessarily] hosted at wint.co... [but] wint.co hosts the JSON document that says where the content currently is".

As "Losing domains is pretty common", however, he explores two more options, both of which "tie you to the same handle forever", which is just a big a problem as tying the user to the same domain - ie, "we want people to be able to change their handles at any time without breaking links... So let’s ... store the current handle in JSON alongside the current hosting," which ends up saying: “Call me @wint.co, my stuff is at https://some-cool-free-hosting.com.".

So for option 4 we bring in cryptographic keys to manage identity, so we don't need a “centralized registry" to register your identity with. It works as follows:

- "When you create an account, we’ll generate a private and a public key.

- We then create a piece of JSON with your initial handle, hosting, and public key.

- We sign this “create account” operation with your private key.

- Then we hash the signed operation. That gives us a string of gibberish like 6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo... That hash becomes the permanent identifier for your account"

So if a link refers to "at://6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5 ... we ask the registry for the document belonging to 6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo. It returns ... your hosting, handle, and public key. Then we fetch com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5 from your hosting."

(the at:// is there as "this isn’t an HTTP link... you need to follow the resolution procedure (get the document, get the hosting, then get the record)").

Combined with some other techniques concerning handle or hosting updates, "the registry is still centralized but it can’t forge anyone’s documents without the risk of that being detected." The registry is also auditable, stores no private data and is entirely open source, and will eventually be spun out to an ICANN-like organisation.

As most people won't do key management, "the hosting "holds the keys on behalf of the user", but you can have an "overriding rotational key... in case the hosting goes rogue."

As "some find relying on a third-party registry... untenable" it's also worth supporting domain as identity, for which they use DID (decentralized identifier). This supports both methods above (option 3 is did:web:wint.co, option 4 is did:plc:6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo), and allows for more.

In summary: "remember four things:

- A DID is a string identifier that represents an account.

- An account’s DID never changes.

- Every DID points at a document with the current hosting, handle, and public key.

- A handle needs to be verified in the other direction (the domain must agree)."

So, "we can finally construct a path that identifies every particular record:

at://did:plc:6wpkkitfdkgthatfvspcfmjo/com.twitter.post/34qye3wows2c5

└─────────── who ──────────────┘ └─ collection ─┘ └── record ─┘

An at:// URI is a link to a record that survives hosting and handle changes. It's also "a unique identifier of every record in our filesystem".

So therefore:

- links are records "in different people’s “everything folders” that each link" to the record they're liking

- reposts are repost records linking to the record they're liking

- replies are posts with a parent post

And your repository is your "little piece of the social filesystem... hosted anywhere... You can move your repository as many times as you’d like without breaking links". You can also "treat it as a stream, subscribing to it by a WebSocket... [so] anyone build a local app-specific cache with just the derived data that app needs."

There are also "dedicated services called relays which retransmit all events", and to ensure you can trust them we "make the repository data self-certifying... structured ... as a hash tree. Each write is a signed commit containing the new root hash. This makes it possible to verify records" without storing them, making relays "affordable to run".

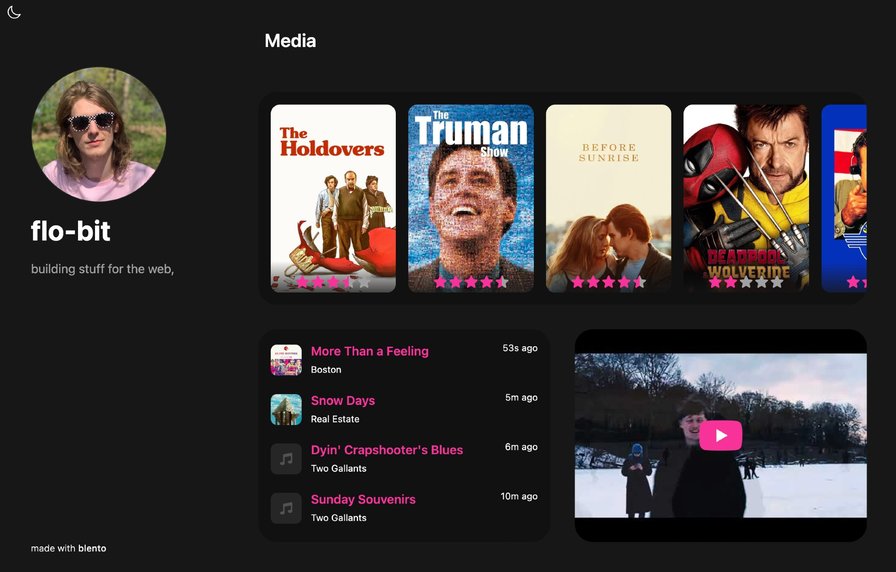

Dan then takes us on a tour of the ATmosphere via pdsls, including via a few videos.

And then asks: "What are files good for? For one, agents really like files" - and shows a video of him "asking Claude to find what my friends have recently made across different apps in the Atmosphere. No API calls, no MCP servers... a glimpse of a post-app future. Apps curate data into experiences, but the web we create floats above every app".

He then demos this using a few pretty technical-looking examples, ending with the "For You" feed, developed by a "3rd party" developer. Except: "In the Atmosphere, third party is first party. We’re all building projections of the same data. It’s a feature that someone can do it better. An everything app tries to do everything. An everything ecosystem lets everything get done."

Read the Full Post

The above notes were curated from the full post overreacted.io/a-social-filesystem/.Related reading

More Stuff I Like

More Stuff tagged atprotocol , guide , social media , unfinished

See also: Bluesky and the ATmosphere , Social Media Strategy , Content Creation & Marketing , Social Web